|

From "Atlantic

Monthly," October 1955.

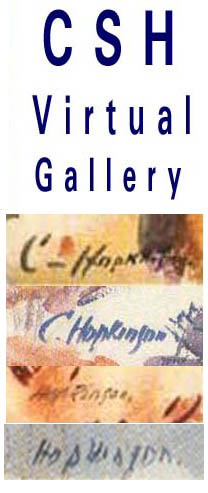

One of the most distinguished portrait painters New England has

produced, CHARLES HOPKINSON painted the leading

lights of Harvard during the administrations of Presidents Eliot,

Lowell, and Conant -- and with such success that his fame spread

far beyond his beloved Cambridge. Now in his eighties and still

painting -- he had a very successful showing of his portraits and

water colors at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston last

-- winter -- his mind harks back to those days when Cambridge was

a country town and when he, an aspirant in his early twenties, was

just getting his start in Paris.

THE

PORTRAIT PAINTER AND HIS SUBJECT

by CHARLES HOPKINSON

1

I

am going to ramble as an old man and tell some of the things which

in these days may seem quaint or amusing, and which will lead

to some of the mild adventures of a portrait painter. In the seventies

and eighties, I should say that the winters in Cambridge were

always white with snow and the air was filled with the sweet tingling

of sleigh bells. A horsecar rushed down Craigie Street with a

big man in a buffalo-skin driving four horses at full gallop,

disappearing in the whiteness of the distance. On a warm evening

in May, the silence of Brattle Street was hardly broken by the

faint trilling of the creatures who dwelt in Smith's Pond, and

then perhaps one heard the romantic sound of young men's voices

singing as they walked out from the College, first faint in the

distance, then growing louder, and then dying away far up the

street. Then silence again.

My

first professional adventure (to call it so) occurred when Miss

Nathurst, who lived next door, seized a portrait of mine, made

perhaps at the age of six or seven -- a drawing of the "Old Man

with the Cows." The man in the portrait used to pasture his three

cows by letting them walk slowly from East Cambridge through Craigie

Street to Mount Auburn and back. It was good pasturage all the

way in the 1870s. Those were happy days when a horse and buggy

could be driven up Brattle Street on either side with not a care

in the world -- unless the horse ran away! For a runaway horse

tearing along wIth dragging reins and a wide-eyed terrified woman

on the front seat was not an uncommon sight.

Miss

Nathurst's cousin, who also lived next door, was Denman Ross,

one of the quaint characters of Cambridge. He had a gentle way

of talking, but had a force in his teaching of art and taste which

was quite remarkable. He painted for his own pleasure and instruction,

and, so far as I know, was the first man hereabouts to formulate

the colors of the spectrum into a language and system which could

be taught and could be employed by any intelligent artist; but

woe betide a pupil who used the stimulation of his teaching to

think for himself and make any change in the system! His monument

is the remarkable Ross Collection at the Fine Arts Museum of Boston.

Other quaint characters in Cambridge were Mr. William Newell,

who would sit at a dinner party with an open umbrella behind him

to keep off the draft, and Mr. Carr, who walked up Brattle Street

with the help of an Alpenstock.

Brattle

Street was either deep in mud or deep in dust, but the fine houses

of Tory Row stood almost alone from Hawthorne Street to Elmwood.

At high tide I used to see the salt water in the grass on the

southern edge of the sidewalk, or watch the tall masts of a Maine

lumber schooner being towed up the river to Watertown. The deep-sea

hooting of the tugboat's whistle echoed among the elm trees and

brought the ocean close to one.

In

Boston, at T Wharf, where the fishing schooners lay three deep,

you could look over the harbor at the big square-riggers anchored

in the stream, or at East Boston, at the delicate tracery against

the sky of the masts and yards and cordage of a full-rigged ship.

Or perhaps, as you glanced to the left, up the harbor you might

see the clipper barque Sarah, with her topsails aback,

sliding out stern first from her wharf for the voyage to the Azores

-- with passengers surely going to visit the Dabneys at Fayal.

At the next wharf, one day, I saw a small foreign looking schooner

unloading salt cod, evidently a French vessel, named the Helene,

and hailing from a place I had never heard of. Five years later

I saw her again at a little seaport town in Brittany as she came

home from the banks of Terre Neuve.

And

that brings me to France and the Art School. It was Julian's,

where M. Bougereau (who now remembers his waxy nudes?) would come,

sit down, say "C'n'est pas mal, mais c'n'est pas assez," and go

on to the next student. One learned by working every day, and

by going to the Louvre. If the studio grew dark, and then the

light came again, the students broke out into the Russian National

Anthem. (That's all I knew about Russia then.) It was really at

the Louvre that one learned -just by being there. I can sympathize

with people who only care for pictures as illustrations of what

interests them, for I was like that even at the age of twenty-one

when I had been drawing and painting marines and landscapes for

many years. At the Louvre a small Dutch picture of a ship was

the only thing which interested me. I went through Holland and

never saw a painting by either Hals or Rembrandt (my present idols),

nor did I enter the National Gallery in London. Then suddenly,

only three years later in Paris, I saw Titian's "Man with a Glove."

(I had probably looked at it often.) The next year the picture

I sent to the Salon du Champs de Mars (the "New Salon" as it was

called) made quite a hit, and the following year there were four

of my pictures there. This seems to me, to whom works of art are

such a great part of my life, a strangely slow development. The

glamour of the world of art in Paris was very strong. One saw

the respect shown the artist even by the shopkeepers, at least

in the Quartier Montparnasse -- yes, and even In far-off Brittany,

where the proprietor of one of those little traveling theaters

in a tent respectfully showed me, a long-haired, beret-capped

youth, a seat reserved "pour les artistes." That was in Roscoff,

a little stony town full of houses built in the sixteen-hundreds,

where Mary Queen of Scots had embarked and disembarked and was

remembered by a ruined chapel dedicated to her.

2

After

the glamour of Paris came life in Cambridge and Boston once more.

The first real portrait I painted was of the poet E. E. Cummings.

He was a baby just old enough to toddle about on the lawn of his

father's house on Irving Street. A boy perhaps seven years old came

across the street to watch me work. When I asked him if he thought

he would ever paint pictures like that, he replied, "I have already

painted pictures which the neighbors consider excellent. I made

a knight in armor which I gave to Professor Norton." "Do you go

to school?" said I, making conversation. "No, my mother teaches

me at home. I used to go to a school where they taught in the phonetic

fashion, so that I spelled nice n-i-e-s." Now I, having heard something

about a Royce boy, asked, "Are you Christopher Royce?" "No. my name

is Edward. Perhaps you have seen in the neighborhood a half-grown

lad in knickerbockers. That is Christopher." Then from across the

street came a mother's voice, "Edward, Edward," and he had to run.

It was a good Cambridge send-off for me.

Life

in Cambridge and Boston included, of course, the instruction and

influence of Denman Ross, and here and there a portrait to paint.

One by one, by painting them, I became accustomed to the characteristics

of Harvard professors; and as a consequence, after some years came

a one-man show in New York.

As

a result of this show, I believe, I had the honor to be chosen as

one of a group of artists to paint celebrities connected with the

Peace Conference in Paris in 1919. Each artist was to paint three,

and as I was the least well known artist in the group, three of

the lesser lights were assigned to me. This was a piece of good

fortune, for they were the most picturesque and could more easily

be induced to pose. Oh! that lovely afternoon in the Paris sunlight

as I walked through the Champs EIysees on my way to meet our Ambassador,

Mr. Henry White, who had kindly agreed to act as go-between for

the artists and their sitters. At the Embassy, when I told him that

I was in a great hurry to get to work, my fellow painter Johansen.

who was in the room, said, "I have had only one sitting from Joffre

in three weeks." Mr. White went with me to call on M. Bratianu,

the Premier of Rumania, my first victim. When he saw Mr. White,

the United States Ambassador. he thought something fine was coming

to him, but though he , was disappointed he agreed to sit next day.

He was a picturesque, sensual-looking man with large red lips and

iron-gray hair cut a la bross -- what we call a paintable

subject. I got ten sittings from him.

Later,

at an interview with the son of Prince

Saionji. the Japanese statesman. I was told that the English

artist asked for only three. So things were until, at the second

sitting of Saionji, his charming daughter (sitting in the room in

costume) said, apropos of nothing, "I think the English artist had

four sittings." So I got four. Prince Saionji, posing stiffly

in his cutaway coat and striped trousers, said "Non" when I asked

him if he spoke English or French. So in silence I worked with furious

speed. Some time later I read, perhaps in the Paris edition of the

New York Herald Tribune. of an interview by the reporter with Saionji,

who, having been educated at Oxford, replied in excellent English.

When I finished the portrait in Boston, I painted him sitting in

a Chinese chair copied from one in the Museum, which seemed appropriate

to what Japan was doing in China just then.

After

that came the portrait of M. Pashich. the Premier of Serbia. "Well,"

said Mr. White. "when I last saw him, he was in handcuffs!" So,

you see, I did have somewhat picturesque and dramatic subjects.

Pashich lived in a lowly and shabby little hotel guarded by two

sloppy, friendly soldiers who reminded me of New England "hired

men." Perhaps Serbians are like that. Pashich was a large, handsome

man with a long square-cut beard which looked as though it were

hooked on over his ears. He was apparently much flattered to think

that his portrait was to hang in Washington. The job went off in

four sittings, just as I could wish. So there I finished, while

my fellow painters were struggling with distinguished diplomats

and generals who would pose only now and then.

The

Peace Conference portraits were all exhibited in New York, and the

one of Saionji seemed to "put me on the map," so that commissions

began to come to me. "Whom are you painting now?" said my uncle,

President Eliot. "Mr. So-and-so," said I, "but I have not yet decided

on the pose." "Ah," said he, "from now on you may have more work,

and I advise you to make your decisions quickly." He was an administrator,

poor man, so how could he understand a mere painter's problems?

And

now, who were these sitters? One was Barrett Wendell, who had taught

me English in college, and upon the model stand he became simple

and almost youthful, telling stories of ghosts he had seen and revealing

other confidences. I have often found that a portrait sitting brings

out the most friendly traits in my sitters. Another portrait I painted

was of Charles Eliot Norton. This was what we call a post-mortem.

I'm sorry I couldn't have done it while he was alive, but I remember

distinctly many of his sayings as he gave his courses in Fine Arts

3 and 4, such as: "When I look down on you gentlemen here before

me, I see in many of your cravats a horseshoe. What more degrading

symbol!" And when he was presiding at a dinner given at the Tavern

Club to the architects of the Chicago World's Fair, he said, "It

is a great honor to us to have with us you who have made an oasis

in the Sahara of American civilization." Up spoke Mr. Adams S. Hill.

"I think it very unfair of Mr. Norton to speak of American civilization

as a Sahayra." "I said Sahara."

Tom

Girdler was a different sort of man. The commission to paint him

came to me beause I had made a successful portrait of a most delightful

gentleman in Cleveland, Mr. William Mather. He was a steel man,

the leading citizen of the city, head of the Symphony Orchestra,

and a refined, handsome gentleman. His office was in the same building

with that of Tom Girdler, another steel man. Evidently Girdler's

people had seen the Mather portrait and wanted the same artist to

do Girdler. We disagreed on almost every topic of conversation.

When I gave him a rest he walked about the studio saying, "This

is the most disorderly room I have ever seen," and when we parted

he declared, "I'll never get into this sort of thing again."

When

Calvin Coolidge wrote, asking me to paint his portrait, he said

that since it was to be hung in an important place he hoped I would

"use the best of materials." He told me how to get to Northampton,

where he was living, by the only train. When I arrived at his house

at 6:20 P.M., he came to the door saying "Hed your supper?" "No."

"Wal, Mrs. Coolidge and I have hed ours but I guess we can git some

for you." He was a good host. He was a good sitter, also, but not

a vain man, for he said of the picture, in which, I must say, he

had a rather sour expression, "Hed fourteen po'trets painted, and

that's the best maouth anybody ever done of me." He was so perfectly

Yankee -- of the same stock as my own -- that I couldn't help liking

him, and so the painting went well.

Among

my sitters was a man of learning in a very important position in

the world, who, when he saw the preliminary sketch I had made for

my own instruction, emphasizing certain peculiarities, got down

from his seat, indignant, saying, "I thought you were going to make

a dignified portrait. If you do a thing like that, I shall certainly

not sit." Surprisingly naive? A very different attitude from that

of Professor "Joey" Beale,

an almost grotesque little man, who was delightfully interested

in every preliminary sketch and caricature I made of him.

3

There

were a good many college professors and presidents who fell prey

to my brush, and it was great fun traveling about and doing my "big

game shooting," as I call it. The biggest game I shot, and the most

beautiful man who posed for me, was Mr. Justice Holmes -- my most

exciting commission, perhaps. He must have been about eighty-seven

years old, with a shock of white hair over his high forehead, and

a fine white cavalryman's mustache, which he could not forget.

One day after he had asked me to stay to lunch, as his secretary

and I walked into the dining room together, he heard us congratulating

the world on some decision toward international peace which we had

seen in the newspapers. He said, "You young fellers don't know what

you are talking about. I remember how, in a cavalry charge, a Reb

slashed at me with his sword. I put my pistol right against his

chest. The damned thing didn't go off. I wish to God I had killed

that man." Now this was very soon after he had delivered the momentous

dissenting opinion favoring the giving of citizenship to Rosika

Schwimmer, a noted pacifist.

Another

day, after asking me to stay to lunch with Felix Frankfurter and

his wife, he went off to be refreshed by listening to his secretary

reading to him "The Confessions of a Chorus Girl." Thus stimulated,

he kept the conversation at luncheon on the high plane of philosophy

and other subjects so far above my head that I could only sit in

silent awe. I am told that when Frankfurter took him to see his

portrait in the Harvard Law School, where he wanted it to hang,

opposite that of Chief Justice Marshall, he said, "that is not I,

but perhaps it is just as well that people should think it is. How

did the damned little cuss do it?" The last time I saw him, a few

months before his death, he was lying on a sofa, weary with old

age, but spick-and-span in dress, with a rosy but very old face.

He said, "I wish you would tell me something about this painter

El Greco!".

Let

me now tell you an anecdote which shows the power of the paintbrush.

I was painting the younger John D. Rockefeller. He sat for me in

his office at his table, far at one side of the room, looking a

little past me to the left. One day he said, "Some men are coming

this afternoon to talk about some very important matters. I hope

you will be very discreet." I told him I should be very busy and

didn't understand anything about money matters, anyway. When the

four men arrived and sat down in the empty part of the room, after

introducing them to me he said, "I am in the hands of my artist

and am sorry I cannot look in your direction, but we may begin."

Presently a preposterously large sum of money was mentioned, perhaps

a hundred million dollars and at that he turned his head toward

them. Silently I waved my paintbrush at him and he was back in his

pose immediately.

My

chief theory is that a portrait should exist in the world of art

and should not resemble a reflection in a mirror. In the first place,

its shapes and outlines should as much as possible (still keeping

a human resemblance) be in a geometrical pattern in harmony with

the dimensions of the canvas on which it is painted. It should have

a color scheme derived from an arrangement of certain tones chosen

from the colors of the spectrum. I keep in mind the advice of a

member of the Royal Academy, Fuseli, who told his pupils not to

copy but to imitate Nature -- that is, to re-create. The

painter should not try to reproduce the colors he sees in his sitter.

Nature's range in light, and therefore in color, is from brightest

light to darkest dark, while the artist's range is only from white

paint to black paint. Therefore the artist must organize his colors

in imitation of the way they are organized in nature. Yellow is

the lightest color, and violet blue or violet the darkest. Perhaps

you could think of it as the keyboard of a piano -- high notes

and low notes with almost innumerable modulations. In darkness we

see nothing. When light falls on a solid object, part of that object

is lightest, another part of the object is darker, and finally the

part farthest away from the light is in shadow. Those tones must

all be arranged in order, in the painter's mind and on the palette.

There

is an excitement in portrait painting. The thing has to be done

with all the tension that one uses in a violent game, keeping this

up for the two hours of a sitting. You have to think and feel at

the same time. Now what is feeling, as the artist uses the word

? I think it is making yourself into the person before you, not

reasoning what sort of person he is, mentally or spiritually, but

being that person as he appears to your eyes -- feeling yourself

resembling him in his gestures, in the way he sits or stands. If

he is a person you don't like, the portrait may be a good likeness,

but it will lack the something which unconsciously gets into a portrait

of a person one is attracted to.

Now

you may ask, "How about painting women and children?" A child, yes.

That is like painting what is lovely in landscape or in a flower.

Perhaps women are too mysterious. Perhaps it is too difficult to

become one as I tried just now to describe "becoming" one's sitter.

I have made two good portraits of women. One was of an elderly philanthropist,

Miss Elizabeth Putnam, and the other is of Dr. Sara Jordan, of the

Lahey Clinic. But both of them had characteristics put there by

great achievements. I am speaking of "lovely women" in quotation

marks -- the kind Romney tried all his life to paint with not great

success. Perhaps the obviousness of feminine attractiveness is disconcerting

and cannot be described by me in terms of painting and the language

(as I like to call it) to which I am accustomed. John Sargent, when

asked why he had not made a better portrait of a lady he had painted,

replied, "What could I do? She is a beautiful woman!" He meant that

there was nothing in her face to emphasize or exaggerate in order

to make a likeness. Nature had made her too perfect.

My

difficulty perhaps is summed up in the comment made on my New York

one-man show by the Art Editor of the New York Sun. " He

is enough of a Yankee to portray a shrewd business man, is at home

with his academic clients, but when it comes to the ladies, he makes

them look good and not dangerous."

|